This is gonna be a long one, folks so make sure you’re sitting in a comfy chair and you’ll probably want to go pee before you start reading but don’t worry, there are pretty pictures. We good? Okay.

In case there are those of you who haven’t been keeping track (shame, shame) I have cleared the one year mark in Madagascar! Not only that, but there hasn’t been a single ET (Early Termination), Medical Separation, or Administrative Separation from my stage! That means all 27 of the lovely volunteers I came to country with and trained alongside for two months in Mantasoa are still here in Madagascarland with me! For those rolling their eyes and mumbling ,”big whoop-dee-doo” I invite you to put down your iPhone, leave your reclining chair, and try living in Madagascar for a year. We’ll see how many meals of white rice you get through before I find you crying in a corner in the fetal position. I’m still not quite sure whether as a group this means we are mentally strong and well adjusted or if it just means we’re exceptionally stubborn – either way I’m proud of our accomplishment. Go us.

This was me a year ago. Oh, how the time flies.

Let’s see…interesting happenings since my last entry. Backtracking to the end of June, a fellow volunteer visited and stayed with me at my site for the first time – even better, it was my former training center roommate Carolyn. Carolyn lives about eight or so hours south of Antananarivo so I didn’t expect her to ever make it out to my site. However, she was coming back to Madagascar after a truly epic vacation in Europe with some friends (totally jealous) so she was in the capital since that happens to be the location of Madagascar’s only international airport. She was in no big hurry to get back to her site because all the teachers in her town are on strike and have been for several months. Since she is an English Teacher, that’s rather inconvenient for her however, it worked out quite nicely for me. Carolyn came to Andramasina and stayed with me for about a week before we both headed back up to the capital. We had a good ol’ time in Andramasina doing basically nothing the whole week. Perhaps one of the reasons why Carolyn and I get along so well is that we both are extremely easy to amuse – it really does not take much. Case in point, one night we discovered a karaoke program on my computer and spent four solid hours drinking beer and singing karaoke with the occasional interpretive dance thrown in – just the two of us. Other days we slept what was likely an unhealthy amount since Carolyn was recovering from sleep debt accumulated during her Eurotrip and I can basically go to sleep anywhere and at anytime. Oh! I almost forgot. The 26th of June is Madagascar’s Independence Day (or in my less than historically accurate mind, the day that Madagascar finally stood up and said, “France, your croissants may be delicious but we want our independence!”). To celebrate the big day, Carolyn and I visited my Malagasy extended “family” in Tana. As usual, there was a lot of dancing and rum involved in the festivities but the best part in my opinion was sitting outside and watching the fireworks show. That’s right…Madagascar has its own fireworks show in the capital on their Independence Day and it is quite impressive. They even had those fireworks that form a smiley face when they explode. No joke. As Carolyn and I sat there – well, I was sitting there and Carolyn was attempting to make friends with every single child within a mile – we were both grateful to be able to share in the Malagasy celebration but also sort of guiltily happy that we could pretend for just a minute that the fireworks lighting up the night sky were actually 4th of July fireworks being watched from some familiar place in the United States.

Carolyn – too legit for life

And then there was the surprise circumcision. I mean, it wasn’t a surprise for the family of the boy (luckily) but rather it was a surprise for me. Generally, I am fairly confident with my Malagasy speaking abilities (if I wasn’t at this point it would be a big problem). However, there are a select few individuals who I tend to inexplicably get choked up around – one of them happens to be Andramasina’s Medicin Inspecteur, Dr. Solofo. That is very unfortunate for me because he is basically my boss at site. In theory, I should probably meet with him regularly and if I did that faithfully he might even invite me to help with various health initiatives in the outlying villages. But in reality, I avoid him like the plague. As in, I hear his booming voice from across the hospital compound and I take it as my cue to scurry and hide like a cockroach. Physically speaking, this guy should not be intimidating – he stands a good head shorter than me and I’m not tall by any means. He has a moustache that I have strong suspicions was inspired by a Mario videogame and he always seems to be wearing black (but not in a cool way like Johnny Cash). But in spite of his appearance, Dr. Solofo manages to intimidate the fire out of me and when he is around all those cool sounding Malagasy words just get stuck in my throat and I’m left silently staring at him with my mouth agape like an oversized goldfish. It doesn’t help that he speaks Malagasy a hundred miles an hour and with absolutely no attempt to avoid difficult vocabulary I might not know. That is all background information leading to the surprise circumcision. One evening, I forced myself to untuck my tail from between my legs and went to speak to Dr. Solofo about helping me find patients who could benefit from cleft lip and/or cleft palate surgery (I’ll elaborate on that later). As usual, he was in a big hurry of some sort and rushed off in the direction of the Health Bureau building as he simultaneously shouted some rapid fire Malagasy over his shoulder. Basically the only thing I got from his spewing of words was, “I am busy right now but walk with me and explain it.” So I obediently trailed behind him and breathlessly tried to explain the project and how I needed him to help me find patients. I was concentrating so hard on explaining it well and in clear, grammatically correct Malagasy that I noticed rather late that we had stopped in a back room of the Bureau and several men had a two or three year old boy pinned to the table. He had no pants on and was clearly (and understandably) having an absolute fit. My less than perfect explanation of the project immediately died on my lips as I stared dumbly at the scene before me. Dr. Solofo immediately swooped in, produced a surgical kit from thin air, and proceeded about his business. Once I realized what was going on, it was too late. Some things you just can’t unsee. The poor kid worked himself into such a frenzy that he was shaking from head to foot. I felt so sorry for him that I ran back to my room and got him a little bag of chips I had bought earlier that day. He took the bag from me while he continued wailing his lungs out. Not that I blamed him. Not one bit.

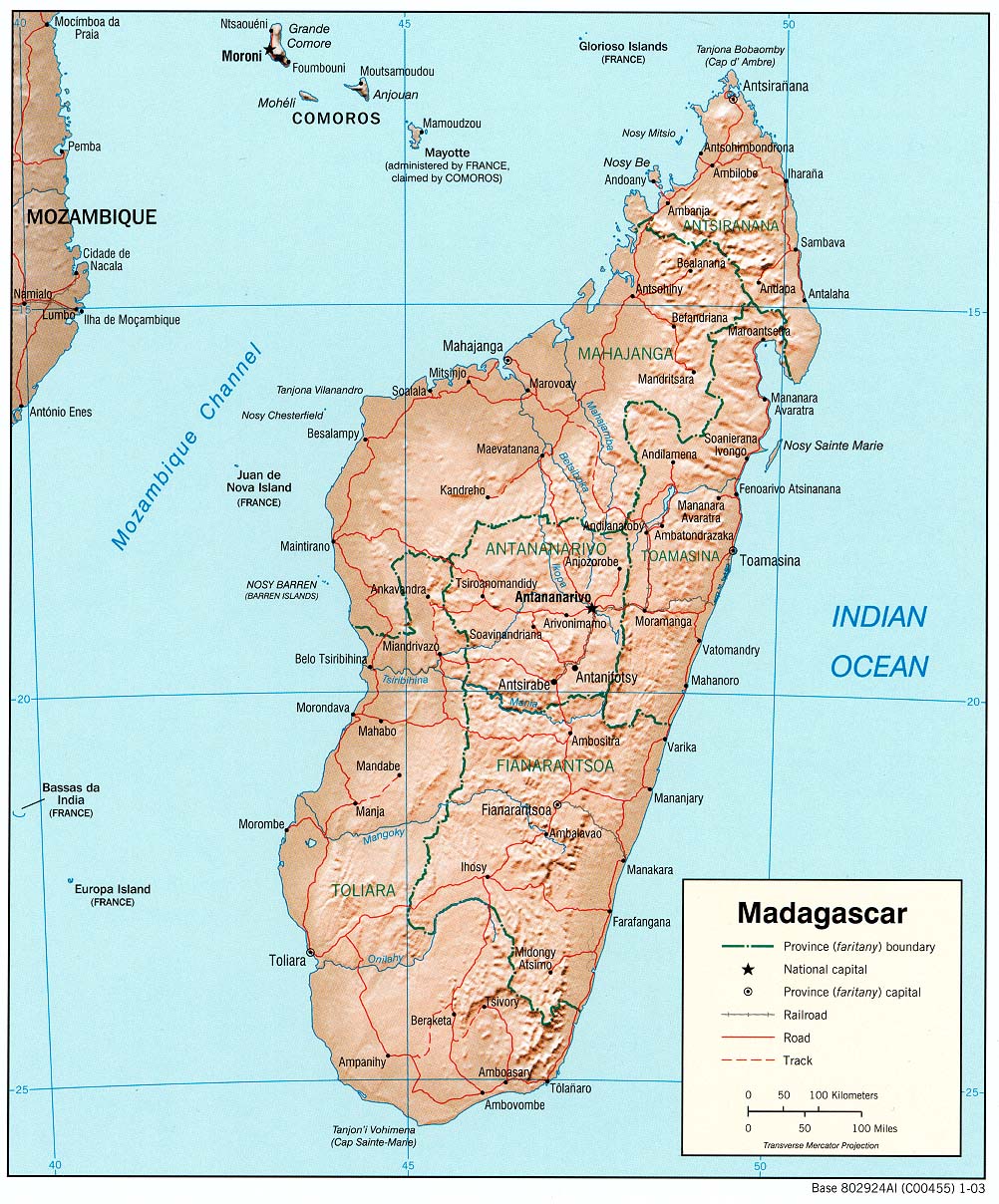

Speaking of circumcision (not a phrase often uttered), the traditional Malagasy circumcision ceremony is actually quite a big to-do. I haven’t gotten wind of any traditional ceremonies occurring in my town, but I hear that they are still very common in some parts of Madagascar, especially the west coast around Morondava. The ceremony is seen as a coming of age and celebration of manhood for the lucky (?) young man. Often the boy is much older than the youngster I saw get snipped at the Bureau – I have heard of ceremonies for boys as old as 10-12 years. The whole community gathers for the event and sometimes gifts are given. But here’s the kicker – if you are part of the Sakalava tribe after the much anticipated snip, the grandfather eats the foreskin. No, I did not make that up. If you doubt me you can look it up. There was even an episode of Bizarre Foods in Madagascar where the show’s host witnessed a traditional circumcision ceremony – foreskin consumption and all. Sometimes the foreskin is eaten on the tip of a banana (still not making it up). I have not yet had the nerve (or stomach) to ask a Malagasy friend why the foreskin is eaten but I’m sure the reason must be rather compelling.

Animal attraction

Moving right along – as you may have noticed, it has been quite a spell since my last blog entry. That’s because I have been unusually busy the past few months. Not long after spending the Malagasy holiday with my fellow PCV Carolyn I travelled a few hours east of Antananarivo to a place called Moramanga. I had been fortunate enough to hear through the Peace Corps grapevine that there was a Habitat for Humanity group going to Moramanga that was in need of some translators. With nothing even remotely compelling going on at my site, I jumped on the opportunity to see a new place and feel at least a little useful. Even better, the other translators for the trip were some of my Peace Corps stagemates – basically guaranteeing a good time would be had by all. I was so excited to have a “real job” and an excuse to go somewhere new that I completely ignored the fact that I essentially knew nothing about the Habitat project for which I was going to act as a translator. I didn’t know who the Habitat volunteers would be, how we were going to get to Moramanga, where we would be staying, what sort of work we would be doing in addition to translating, or basically any useful information. All I knew was that we would be in Moramanga for ten days and that we were supposed to meet the Habitat group at the Radama Hotel in Antananarivo on July 14th. Luckily for highly uninformed me, it all worked out just fine. The Habitat volunteers were a diverse group of people (although the vast majority were American) who were eager to get their hands dirty to help others – so needless to say, they were pretty great. Most of them had participated in Habitat builds in foreign countries before so they really knew what they were doing. The goal was to build five new houses in ten days. Impossible? No. Difficult? Oh yeah. As I discussed in a previous entry, Madagascar gets hit pretty hard by cyclones every year so some of the houses we were building were actually for families who had their homes destroyed when Hurricane Giovanna threw a temper tantrum all over Madagascar. I quickly discovered that being a “translator” really meant that I was an additional builder who occasionally clarified something shouted in Malagasy. I did manage to pick up some nifty new Malagasy vocabulary during the build although I’m still not sure how to work words like mortar, trowel, and gravel into daily conversation. I’ll work on it. In addition to the odd translation or two and helping with construction I found that I somehow landed the role of child herder. I call it herding because that is honestly the best description I can come up with. A large group of “vazaha” building a house in the middle of a Malagasy village unsurprisingly drew a rather large crowd of miniature onlookers. Since they clearly had nothing better to do, I decided to see if they wanted to help. The answer was an enthusiastic (if chaotic) yes. After some trial and error and many repeated explanations of how to form a proper line I finally got my little minions to stand in a (rather squiggly) line and pass bricks one by one. A small feat perhaps but one which I was pretty darn proud of. As a sort of reward for their toils, every day at 4pm (one hour before we stopped working) I would gather my little flock and teach them either a song or dance. I will say that the kids in Moramanga are much better at the Hokey Pokey than my English Club students in Andramasina. Major kudos. As is true with most enjoyable experiences, the ten days passed all too quickly. We weren’t able to finish the five houses but most of them were only lacking the finishing touches – these would be completed by the Malagasy construction workers after the Habitat group departed. So in conclusion, building houses and herding small children in Moramanga = pretty awesome experience.

Some of the amazing Habitat volunteers I worked with

My “flock” of children

- This Habitat volunteer (Benny) was Peace Corps 1961!

After being so productive for ten straight days it was kind of a shock to return to my site and the often frustratingly slow pace of life there. I didn’t have to wrestle with loneliness and boredom very long however because the very next week I had four “baby” volunteers to entertain. You may recall that when I arrived in country I had to complete about two months of training before actually becoming a volunteer. The training is meant to prepare you for your two years of service by providing language instruction, cultural sessions, and generally giving you some time to dip your toes into the Peace Corps pool before doing a cannonball into the deep end. During training here in Madagascar there is also something called “demyst”. This is a period of a few days when the baby volunteers are sent out in small groups to stay with current volunteers at their sites and learn the ins and outs of Peace Corps daily life – using a kabone, fetching water, being stared at, avoiding piles of zebu poop while walking – all the essentials. After a persuasive call from Tovo, I somewhat grudgingly agreed to host two babies at my site (although I actually ended up with four – long story). Don’t get me wrong, I love the idea of hosting trainees and having a full circle moment but it made me late for Operation Smile (more on that in a hot second). With everything now said and done however I am glad that I had the opportunity to host the babies – their bright eyed eagerness rekindled a bit of the old excitement in me. I remembered for the first time in a long while how it felt to have the whole of my Peace Corps service stretching out before me full of unforeseeable challenges and endless potential. I realized that although I am halfway finished with my service there are still so many wonderful possibilities to explore with the time remaining. I still have a lot to be excited about.

The baby volunteers with my Malagasy “grandma”

Okay, so as promised I’ll finally elaborate on Operation Smile. Remember the surprise circumcision? Of course you do. Now remember how I was trying to talk to Dr. Solofo about finding cleft lip and cleft palate patients? Yeah, that was for Operation Smile. In a nutshell, Operation Smile is an organization that sends doctors, nurses, dentists, and other medical personnel to developing countries to perform cleft lip and palate surgeries. The really awesome part is that everything is completely free of charge for the patient – the surgery, a bed to sleep in, and even meals if required. An Operation Smile team has been coming to Madagascar once a year for a while now and every year they request the help of some lucky Peace Corps volunteers to act as translators. As a health volunteer I had priority over volunteers from other sectors (sorry, guys) and I was fortunate enough to be selected to help out. So that is how I found myself unwillingly and unexpectedly witnessing a circumcision – I was simply trying to find people around my site that could benefit from the surgeries. And that is also why later I was so reluctant to take baby volunteers for “demyst” which would make me late for my role in Operation Smile. You see? It all comes together in the end (oh yea of little faith). As it turns out, being a few days late for Operation Smile didn’t make a huge difference. Although we all signed up on a nice pretty sheet for specific translating jobs on specific dates at specific times, we all just sort of showed up and filled whatever slots needed filling – a little inefficient but that’s Peace Corps for ya.

One of the happiest little kids I’ve ever met

My first day of translating was also my longest day – 16 hours from start to finish. The doctors and nurses (who were from all over the place but the majority were South African) informed us that the first day is generally the longest on any given mission. I was working in the Recovery Room means that I was there when the patients were first brought out of surgery (the little ones often being carried in the arms of the surgeon). The absolute best part of my job was going to get the mother (or sometimes father) from the waiting room and brining them to the patient’s bedside. When a new patient arrived in the Recovery Room, I would sort of hover on the periphery as the medical personnel checked the various monitors and conversed urgently in seriously cool sounding medical jargon (made even cooler by the South African accents). Eventually, the head doctor would notice me fidgeting and say, “you can go get the parent now” and off I would scurry to the room of anxious, expectant faces. After calling the patient’s number one of the parents would jump up, eyes as round as bowls of rice and practically quivering with nerves. The first thing I always told the parent was that everything had gone well during the surgery and that they shouldn’t be scared (which was true because nothing went seriously wrong during any of the surgeries). Then I would guide them on the short walk to the Recovery Room where parent and child were reunited. Parents reacted to seeing their children after surgery in various ways. Most were fairly quiet and reserved (that’s Malagasy culture) but a few memorable ones cried tears of joy and one mother walked right up to the surgeon and hugged him (FYI Malagasy do not hug so this was really exceptional). After the initial reunion however, my job got a little less fun – mainly because the anesthesia started to wear off and the kids realized that they were in a strange place with strange people and their mouths hurt. As you might imagine, a rather unpleasant noise often ensued. It was my job to translate specific instructions to the parents on behalf of the medical personnel and occasionally give a syringe of juice to a wailing child while simultaneously staying out of everyone’s way. This was of course easier said than done – the trick was being where you were supposed to be when you were needed and at all other times staying out of the line of traffic. More than once I was shooed away from a bedside by one nurse only to be immediately called over to the exact same location by another. Unlike the Habitat build which was (for obvious reasons) physically exhausting, Operation Smile was often mentally and emotionally exhausting. But it was also immensely rewarding. Being able to witness what these selfless and clearly very skilled medical professionals could do for their patients was spectacular. I would see children go into surgery with a horribly disfiguring cleft lip and come out a few hours later with an entirely new face and only a tiny line of stitches betraying that any sort of surgery had occurred. While the cleft palate surgeries were less visually dramatic, the difference they make in the lives of the patients is simply amazing. Most children with uncorrected cleft palates will never be able to eat or speak properly. The hole on the top of their mouth causes food to exit through the nose while eating and leaves no place for the tongue to maneuver adequately in order to form the complex sounds that make up human speech. Many children born with cleft palates in developing countries don’t survive the first year – and if they are one of the few to survive their speech and subsequent developmental impairments make for a very difficult and isolated life. It is obviously much more effective and thus preferable to correct cleft palates at a young age – generally the older patients who showed up during Operation Smile were not good candidates for the surgery. However, they were not simply turned away. Cleft palate patients who were too old for the surgery were fitted with something called an obturator. Although I never saw one myself, I gather that it is a small device that is fitted to the gap in the palate. In essence, it acts like a prosthetic palate, preventing food from entering the nasal cavity and aiding in speech formation. What I just described may not be fascinating to all, but I personally think it is downright miraculous. Major altruism points to Operation Smile.

A relieved mom holding her daughter after surgery

But all work and no play makes for a horribly dull individual so what better way to wrap up all this unprecedented productiveness than with a fabulous vacation? Clearly, there is no better way – enter the fabulous Pasha Feinberg, awesome friend and “sister” from my days at Stanford University. This lady flew halfway around the planet just to visit me (although I suspect the prospect of seeing lemurs might have had a tiny bit to do with it as well). At the present time, there is no word in the English language to properly describe just how excited I was to greet her at the Tana airport. Think of the most excited you have ever been in your entire life and then multiply it by about a gazillion – yeah, that excited. The manner of my arrival at the airport was a bit of a surprise. I had of course told my Malagasy family that I had a friend visiting me from America. Vonjy is the only one in the family with a car so I asked if he could help me pick Pasha up from the airport with the understanding that we would pay for the gas. What I had not anticipated was that the entire family would want to go to the airport to greet the new “vazaha”. The solution? They rented out an entire taxi-be (basically a small bus) to shuttle us all to and from the airport. So when an extremely exhausted Pasha rolled into the airport arrival area she was not only greeted by me but by about a dozen over-excited and slightly inebriated Malagasy she had never met before. Pasha, although a little shell shocked, managed to take it all in stride. If our places were reversed I might have run screaming back to the plane.

“Sisters” reunited! 🙂

And thus began the grand Madagascar vacation adventures of Pasha and Kim. We spent the night in Tana and then made our way to my site, Andramasina. I got to show off my sleepy little town to her and most importantly, the cutest dog in the world – Lolo. Lolo immediately showed her affection for Pasha by curling up on top of a pile of her clothes and getting dog hair all over everything. When we left Andramasina to head south Lolo sadly and rather pathetically watched out taxi-brousse drive away (don’t worry, Vatsy takes care of her when I am away). We made it to Antsirabe that day and stayed at a favorite Peace Corps locale, Chez Billy. At five fifteen the next morning (so painfully early) a taxi-brousse was waiting to take us even further south to Fianarantsoa. Once we arrived in Fianar we were able to change brousses and backtrack on the road about an hour and a half to our desired destination – Ranomafana (literally meaning “hot water” because of the natural hot springs there).

Ranomafana = gorgeous

Ranomafana is one of Madagascar’s major National Parks and home to quite an array of lemurs, chameleons, frogs, and other appealingly cool creatures. We were fortunate enough to find a cozy little hotel owned by an older man who told me everyone calls him “Dada Fara”. The nice (although a tad absentminded) owner also happened to know a very good English speaking guide who met with us that evening and made arrangements to be our guide in the park the following day (you aren’t allowed to enter the park without a guide). Pasha and I rather ambitiously agreed to a six hour hike through the park. The hike ended up being truly breathtaking – in more ways than one. The scenery was undeniably gorgeous and it was thrilling to chase our guide through the forest as he tracked lemurs and birds but in retrospect I should have done a little preparation beforehand for such a difficult hike. As in, I should have gotten off my lazy rear and walked a little bit before deciding to hike through the Madagascar rainforest for six hours chasing fast, furry mammals. Clearly, both Pasha and I managed to survive the ordeal (somehow) but soreness stayed with us for quite a few days, reminding us of our lapse in judgment. The lemur spotting made it all worthwhile however – we managed to see Golden Bamboo Lemurs, Greater Bamboo Lemurs, Sifaka, and Red Bellied Lemurs. And my personal favorite part came at the very end when we hiked down to an absolutely gorgeous waterfall and I went swimming at the bottom – clothes and all. It was the first time I had gone swimming in over a year and I couldn’t have asked for a more beautiful locale.

Yeah, I swam in that waterfall. No big deal.

After the loveliness of Ranomafana, returning to Fianar was sort of a drag but it was the only way we could get down to our next destination, Anja Park – a tiny little community initiated and run park to the south of Fianar that is only on 8 hectares of land but has an impressive population of 400 Ring-tailed Lemurs. A fellow Peace Corps volunteer (environment sector) actually works down there and told me that the Ring-tails had recently given birth, which was enough to work Pasha into a frenzy and guarantee that Anja Park would be on our travel itinerary. Getting there proved to be a might tricky since there are no taxi-brousses that go directly to Anja. However, following the advice of the volunteer we were able to have a brousse going farther south to Ihosy drop us off at the park entrance. Our hike at Anja Park was only about three hours long but had its own challenges. The trail in Ranomafana National Park had been almost comically difficult, but at least it was clearly marked. The trail in Anja Park started out clear and promising as it winded through some shrubs and small trees but quickly disintegrated into a mass of gigantic boulders to scramble over and around. I happen to enjoy a good adventure, a little off-road trekking, taking the path less travelled and all that – but this was more like the path not travelled for a reason. It’s generally not a good sign when your first reaction upon seeing the obstacle in front of you is, “Aw, hell no.” That was precisely my mental reaction at several points during the trek, particularly when we were required to walk over a slippery rock surface at a ludicrous angle with death or disfigurement awaiting those who fell. When I was brave enough to chance a glance down the abyss awaiting me if I slipped I half expected to see little gravestones at the bottom marked, “Here lies another vazaha.” Eventually I think I either became accustomed to a constant level of fear for my life or I went a little insane from the stress because when I spotted a rope trailing down a rock face that we were clearly supposed to repel down I just laughed and shouted, “Pasha! You’re not gonna believe this!” Granted, this was not a very great distance we were required to repel down. But to have it just suddenly pop up on the trail like “surprise!” was both absurd and hilarious. Eventually, both Pasha and I managed to repel down the tiny rock face although Pasha chose a rather unconventional method for repelling – she somehow scooted all the way on her butt. This of course was all to the great amusement of our two Malagasy guides who I’m sure will tell stories of the “butt-scooting vazaha” for years to come. Throughout this entire trek, we did manage to see some Ring-Tailed Lemurs and even spotted one with a tiny little baby clinging to its stomach. However, the vast majority of the lemurs were sleeping when we passed through because we just so happened to arrive at the park during lemur siesta time. Fail.

At least this guy was awake

After our epic hike in Anja Park we returned to Fianar for the night and caught a taxi-brousse early the next morning heading north, all the way back up to Tana – a ten hour trip. Fortunately, the taxi-brousse wasn’t nearly as crammed as they usually are otherwise the trip might have been unbearable. Besides getting a very sore rear end from ten hours of jostling the trip was relatively uneventful. We rolled into Tana tired and dirty just as it was getting dark and spent the night at my “aunt” Lolona’s house. The next leg of our journey took us to the east to Moramanga (if that sounds familiar it’s because that is where I built houses with Habitat). It was at this point I believe we began wondering just what percentage of our trip we had spent travelling in taxi-brousses. Not a whole lot to do in Moramanga but they do have some truly excellent “frip” (secondhand clothes markets). And more importantly, I got to revisit the houses we had built during Habitat. At the end of the Habitat trip the five houses were pretty far along but missing the final touches. The Malagasy carpenters had continued work after our departure and it was really satisfying to walk around Moramanga and see the nearly finished houses. Better yet, some of my little minions remembered me and after about five minutes of walking Pasha and I had gathered an entire flock. Curiously enough, some of them had picked up stilt-walking (you can’t make this stuff up) and were following us around on hand made wooden stilts thus adding to the appearance of a small parade going through Moramanga. Good stuff.

Me standing in front of one of the nearly finished Habitat houses

Our final destination was reached the following day – Andasibe. Andasibe National Park is even bigger and more developed than Ranomafana and has the distinction of basically being the only place in the world to see the largest lemur species – the Indri (or babakoto in Malagasy). If you’re thinking, “Oh, big deal…I’ve seen an Indri before”, no you haven’t. Not unless you happened to be in Madagascar at the time. Indri can’t survive in captivity because their diet is so specific. They only feed on trees that are endemic to Madagascar and they eat approximately 32 different kinds of leaves on any given day. So short of transplanting a few hectares of Madagascar to a zoo Indri are impossible to maintain in captivity, which is really quite a shame because they are pretty awesome. They are the biggest lemur species, the only one without a tail, and they make a noise that can be heard three kilometers away.

Indri, or babakoto

Pasha and I arrived a little late to Andasibe so we spent the first day just exploring a little and walking to the park entrance. We met yet another awesome Malagasy guide whose English was superb and he suggested we go on a “night walk” to see chameleons, frogs, and the elusive Mouse Lemur. Since we had no plans for the evening and the prospect of seeing a Mouse Lemur was hugely appealing, we decided to go for it. There was something especially exciting about walking around at in the dark of night searching for wildlife as light rain fell. It gave the trek an extra little hint of the exotic that allowed me to feel like I was taking part in a National Geographic documentary – at least until some other vazaha being led by a Malagasy guide passed by us and shattered my illusion. Pasha and I were convinced that our guide was a “chameleon whisperer” since he managed to spot a ridiculous number of chameleons that were sitting absolutely motionless and imperceptible on branches. He even pointed out several of the tiniest chameleons in the park; they were barely the size and width of a pinky finger and they were often exactly the same shade of brownish green as the branch they were flattened against. I’m still not entirely convinced our guide didn’t have those chameleons super glued in strategic locations that he then memorized. He was that good. Our night walk did yield a few glimpses of the tiny and absurdly cute Mouse Lemur but those buggers are quick. Rather unexpectedly, our guide managed to find a Wooly Lemur doing its best to hide from our flashlights in a tree. I can’t exactly say the Wooly Lemur was cute – it rather reminded me of Golem from the Lord of the Rings, but very cool nonetheless.

Andasibe – how I love thee

The next day we met up with the same guide who had led us on the night walk to explore the actual park. We opted for a four hour hike which surprisingly ended up being the least physically taxing of our various hiking adventures. It didn’t take long at all for our guide to locate a family of Indri sleeping very high up in the treetops. Then all we had to do was wait for them to wake up, come down, and start their morning calling. As it turned out, we didn’t have to wait long at all – almost as soon as we spotted them they started to descend. The calling noise they make is difficult to describe. Imagine a cross between a gibbon call and whale song and then make it really freakin’ loud. That’s the best description I can give of an Indri call – haunting and beautiful but a little painful to the eardrums in close range. We saw lots of other lemurs during the Andasibe hike but I really think the Indri was the most impressive. Although we did see some Sifaka with a tiny little baby that was too adorable for life. At one point the baby tried to leave its mother and go climb on a branch but the mother and father took turns shoving the baby back towards the safety of its mother’s belly. Better luck next time, little Sifaka. So in addition to the Indri and Sifaka we were fortunate enough to see Common Brown Lemurs (which are my personal favorite now) and the Grey Bamboo Lemur. For those of you who are keeping score, that brings the lemur species count up to eleven. Three parks and eleven lemur species, not too shabby. We also saw more chameleons, a gecko, and some pretty birds but let’s face it, the lemurs are much more exciting.

Sifaka and tiny baby!

That pretty much wraps up the most thrilling parts of the Pasha and Kim Madagascar adventure. We did return to my site briefly to pick up one of Pasha’s bags and check on Lolo (who greeted us with her epic wiggle dance). Then we went to Tana once more. Pasha’s flight wasn’t until one in the morning so we had some time to kill. We considered going to a zoo called Tsimbazaza which according to the guidebook Pasha brought has some of the lemur species we didn’t get to see as well as a fosa but unfortunately the weather was not in our favor. It’s probably a good thing we didn’t try to navigate the bus system in Tana to get to the zoo. At one point we found ourselves on a bus that dropped us off in the middle-of-nowhere-outskirts of Tana and we had to walk an hour just to get back to where we started from. Unfortunate for sure, but not an unheard of occurrence when Pasha and I attempt to go anywhere – it’s really remarkable things like this didn’t happen more often during our travels. I did take Pasha to a little vazaha market near Analakely where she picked up a few nifty souvenirs for the folks back home. Of course, since this market mainly caters to vazaha looking for souvenirs the prices were a little out of control but luckily Pasha happens to be pretty adept at bargaining. Eventually, the inevitable came to pass and Pasha had to be taken to the airport (somehow my Malagasy family once again secured the use of a bus for this purpose). I have never had an anxiety attack before but I think I came pretty close to one as I watched Pasha roll her bags towards the departures gate. As sad as it was to say goodbye to my “sister” I am eternally grateful that she was able to make the epic voyage and spend a little time here in Madagascarland with me. If anyone else is interested, I’ll be here another year, so no rush :).